☰

☰

![]()

Kobe Van Cauwenberghe - electric guitar, nylon string guitar, bass guitar, synths, voice

Frederik Sakham - double bass, electric bass, voice

Elisa Medinilla - piano

Niels Van Heertum - euphonium, trumpet

Steven Delannoye - tenor saxophone, bass clarinet

Anna Jalving - violin

Teun Verbruggen - drums, percussion

Recording: at Werkplaats Walter, Brussels

Mixing: Nicolas Rombouts (Studio Caporal)

Mastering: Uwe Teichert

Production: Kobe Van Cauwenberghe & Rogé for el NEGOCITO Records

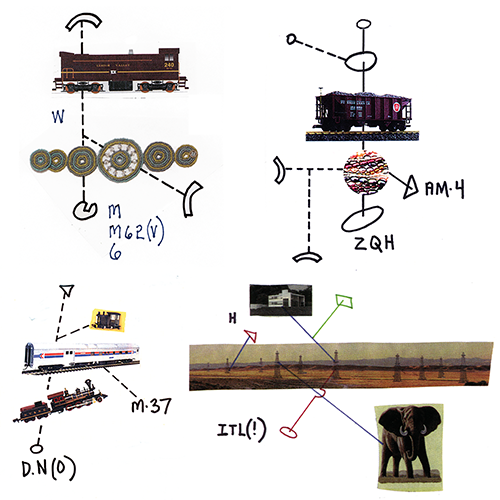

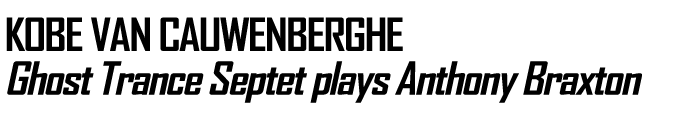

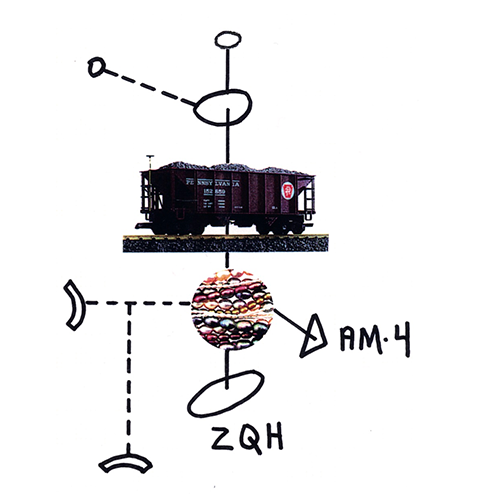

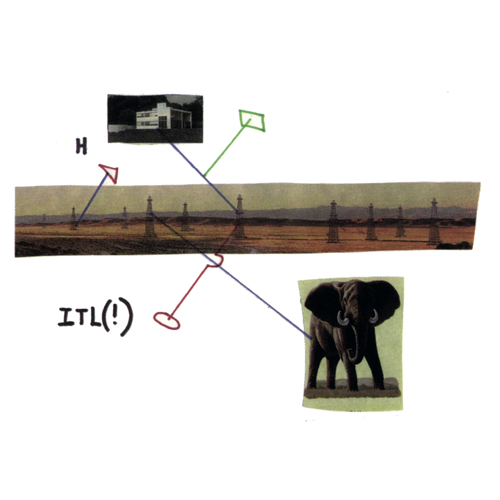

Art work / Title images: Anthony Braxton, courtesy of Tri-Centric Foundation

Lay-out: Jan De Wulf

Band photo: Kobe Wens (Rainy Days - Luxembourg, 2021)

In loving memory of Hugo De Craen (1951 – 2021), friend and friendly experiencer.

Available on double CD / double Vinyl

release double CD June 2, 2022

(ENG)

Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music lets you step into a ritual, guided by a melody without beginning or end, a stream of consciousness that serves as the central track leading into the unknown. The Ghost Trance Musics are specifically designed to function as pathways between notation and improvisation, between past, present and future, unifying Braxton's entire fascinating musical universe. It allows for a plurality of musical practices to join forces, a trance-idiomatic arena in which Braxton helps curate intuitive experiences for both performers and listeners.

Recognising the uniqueness and almost unlimited potential of Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music system, Belgian guitarist Kobe Van Cauwenberghe made it a personal mission to come to a deeper understanding of GTM and its implications for the interpreter. After his acclaimed solo album (Ghost Trance Solos, ATD10), Van Cauwenberghe invited a group of musicians to take a collective deep dive into Braxton’s musical wonderland of the Ghost Trance Musics and explore its unique communal aspects. In the summer of 2021 this Ghost Trance Septet recorded four GTM-compositions, covering the entire spectrum of the four different ’species’ of the GTM system. The result is the present double album.

The musicians of this Belgian-Danish septet have excellent reputation, whether in the art of improvisation, the interpretation of new music, or both. Braxton's work is made for exploratory instrumentalists with such expertise. After the Ghost Trance Septet's performance at the rainy days Festival on November 13, 2021 in Luxembourg, the composer (who was booked for a trio concert at the festival) was sitting in the audience and could hardly contain himself with emotion and excitement. Understandably so. I dare say he had never experienced his GTM concept from the listener's perspective as varied, elaborate and fluid as on that day.

The Ghost Trance Septet does everything right on this production. Whereby "right" is not meant in the sense of correctness, which Braxton dismisses in his recommendations to performers above, but in the sense of astonishing creative, daring, lustful, sensitive, and thrilling. How to play Braxton? Whoever holds this album in his hands can put a very convincing answer on the record player. Over and over again.

- - Excerpt from Timo Hoyer’s liner notes (Timo Hoyer is author of the book Anthony Braxton – Creative Music, Wolke Verlag, Hofheim 2021)

Full Liner Notes

How to play Anthony Braxton?

Anthony Braxton, born 1945 in the South Side of Chicago, is

undoubtedly one of the most innovative composers, multi-

instrumentalists and music theorists of our time. In the

introduction to his Catalog of Works, published in 1989, he

wrote down some general notes on how he would like his

compositions to be treated. Since then, his body of work has

undergone immense expansion and numerous astonishing

twists and turns. However, the recommendations he made to

all potential performers and interpreters remain unchanged:

“a. Have fun with this material and don’t get hung up with any

one area

b. Don’t misuse this material to have only ‘correct’ performances

without spirit or risk. [...] If the music is played too correctly

it was probably played wrong.

c. Each performance must have something unique. [...] If the

instrumentalist doesn’t make a mistake with my materials, I

say ‘Why!?’ NO mistake -- NO work!’ If a given structure concept

has been understood (on whatever level) then connect

it to something else. Try something different -- be creative

(that’s all I’m writing).

[...] and be sure to keep your sense of humor”.

Some of Braxton’s compositions from the seventies, which

he wrote mainly for his working bands (quartets, quintets),

have been interpreted relatively frequently by other musicians

over time. They now belong to the extended canon of

contemporary jazz. These pieces are only a tiny part of his

complete work, which number no less than 700 compositions,

including pieces for solo music, for duo, small and large

ensemble, small and large orchestra, choir, puppet theater,

dance performances and opera. We can consider ourselves

fortunate that Braxton himself tirelessly ensured that he was

able to perform as much of his “material” as possible and document

it on recordings.

Recordings of his works without his participation are, for a

composer of his outstanding stature, somewhat rare. His

compositions can be found on about sixty albums by other

musicians, mostly titles from his early work period, namely

the aforementioned quartet works. That’s a modest response,

one might think, considering the incessant flood of jazz releases

which include, for instance, tracks by Charlie Parker,

Thelonious Monk or John Coltrane. Comparison with the

standard-setting classics of modern jazz is inappropriate,

however. Braxton’s compositional oeuvre certainly contains

distinctive jazz components, but taken as a whole he moves

very confidently outside the jazz idiom from the very beginning

and outside any other known musical idiom as well. He

speaks of the transidiomatic essence of his work, which he

aptly calls creative music. Perhaps its most striking characteristic

is the infinitely inventive blending of notated, partially

fixed, intuitive and improvised components.

In his extremely idiosyncratic, uncompromisingly advancing

work he is primarily concerned with divergence, diversity,

transformation and restructuring (and consequently less

with homogeneity, preservation and consolidation). He has

never allowed himself the slightest bit of nostalgic recollection

or stagnation throughout his career of over fifty years. His

quoted advice to the interpreters of his music, “if a structure

concept has been understood then connect it to something

else”, corresponds to his own handling of compositions and

models. He uses them as aesthetically sophisticated modular

systems. Each one has a specific identity, but can also be

fragmented, restructured, and combined with every other

piece of his system. His hope is that the collage or synthesis

of his material will provide the players with fresh experiences,

surprising discoveries, and environments for creative participation.

Braxton’s musical world is well thought-out and at the

same time thoroughly enigmatic, a universe of incalculable

possibilities, unpredictable, open, yet completely free of arbitrariness.

None of his numerous structure concepts has fascinated and

captivated him as much as the Ghost Trance Music (GTM).

This model marks the beginning of his creative period of

Tri-Centric Modeling in the mid-nineties, which continues

to this day. The core of Tri-Centric Modeling consists of a total

of twelve music “prototypes”, not all of which have yet been

completed. The GTM has an important role in it, as it forms

the musical heart or ground floor of the whole. Between 1995

and 2006 Braxton completed 138 compositions from this

prototype. GTM encompasses a variety of musical traditions.

Inherent in it are the Ghost Dance rituals of the Native Americans,

which can last several hours, the repetitive continuums

of Minimal Music, the rhythmic diversity and trans-tonality

of African music, the parallel sound events of street parades,

the intensity and improvisational passion of jazz, and much

more. GTM is nevertheless anything but an eclectic mix of

styles or genres. It is an unmistakably independent concept

from Braxton’s creative workshop.

The scores, which can be up to eighty pages long, generally

consist of two parts. In the main part, the so-called “primary

melody” unfolds. Usually, a performance begins with all instruments

playing it in unison. This can go on indefinitely

(Braxton dreams of night-long performances), but it can

also be broken up after a few minutes or even seconds, as

determined by the ensemble. The second part of the score is

a short appendix containing “secondary material”. These are

mostly three or four six-line miniature compositions. Braxton

expects a creative, quite liberal handling of the material.

In the notation of the primary melody suggestions are made

(always with the option to ignore them), at which points of

the performance one could move away from the main route

to the paths of the secondary material. These options are indicated

by triangles placed in the head of a note. And there

are more symbols as well.

If a square is visible on a note, it signals to the performers that

they can include passages from any of Braxton’s compositions.

The musicians select this “tertiary material” in advance

and then decide during the performance with whom from

the ensemble they want to interpret something from it. Finally

a third symbol, the circle, signifies that the performers

may engage in a period of improvisation. Again, they decide

during the performance whether or not they actually want to

improvise alone or with others. Braxton’s understanding is

that GTM is not a platform for extensive solo improvisation.

He hopes for imaginative, incisive contributions that are in

service of the overall sound architecture. Van Cauwenberghe’s

Ghost Trance Septet follows this guideline on this record

with bravura. All of the musicians have their spotlight moments

on this album. But no one tries to advance themselves

into the foreground with soloistic extravagances.

The GTM model has undergone substantial changes during

Braxton’s eleven years of involvement with it. There are at

least four different manifestations, which are called “species”,

with one exponent of each heard on this release. The differences

primarily concern the primary melody. The first GTM

compositions radiate a strict regularity, the – in the score not

predefined – tempo is consistant, the beat steady. With each

species this regularity is rhythmically shaken up. In the most recent compositions, the melody is made up of a number of

rapidly swirling figures that have as much to do with a trance

state as a roller coaster ride has to do with yoga exercises.

Braxton conducted a GTM ensemble for the last time 2012 at

the Biennale Musica in Venice. Since then, he has drawn on

the 138 compositions in other conceptual contexts, but the

GTM model as such is history for him. Who will carry it into

the future? Until recently, the younger generation of creative

musicians did not seem to show interest in the model that

one might have expected in view of its overwhelming potential.

But the tide is gradually beginning to turn. We owe this

not solely, but in the main, to Belgian guitarist Kobe Van Cauwenberghe.

In 2020, on his CD Ghost Trance Solos (ATD10),

he managed the feat of creating sparks out of the intricate

structures of GTM as a soloist. Inevitably, one began to wonder

what this fabulous musician, trained in contemporary

composed and improvised music, might be able to pull out of

the model with an ensemble of like-minded musicians. Now

we know!

The musicians of this Belgian-Danish septet have excellent

reputation, whether in the art of improvisation, the interpretation

of new music, or both. Braxton’s work is made for

exploratory instrumentalists with such expertise. After the

Ghost Trance Septet’s performance at the rainy days Festival

on November 13, 2021 in Luxembourg, the composer (who

was booked for a trio concert at the festival) was sitting in the

audience and could hardly contain himself with emotion and

excitement. Understandably so. I dare say he had never experienced

his GTM concept from the listener’s perspective as

varied, elaborate and fluid as on that day.

In Luxembourg the septet performed Composition No. 255.

On this extraordinary studio recording this composition extends

over the first side. At the beginning we are drawn into

the stoic lockstep of the primary melody, which staggers at

certain intervals, indicating that No. 255 is an example of the

second GTM species. Shortly before the unison is about to

dissolve for the first time, after about three minutes, numbers,

syllables and words can be heard briefly spoken or if you will,

sung. That means that this piece also belongs to the subspecies

of Syntactical Ghost Trance Music, whose onomatopoetic

libretto can be executed in whole or in part, or ignored (a

fully sung choral version can be heard on Braxton’s box set

GTM (Syntax) 2017 (NBH908), an entirely instrumental version

for instance on GTM (Iridium) 2007, Vol. 2 (NBH025);

the recommendable comparison of the versions reveals a

lot about the elasticity of Braxton’s compositions). It is pure

pleasure to listen to the septet as it strings together one sonic

shape-shift after the other. Braxton’s older compositions

are skillfully, yet often discreetly, incorporated into the meandering

stream – the highly accelerated No. 34, the quartet

earworm No. 40f as well as No. 168, once written for a duo

session with James Emery – in order to flow smoothly into

the home port of the primary melody.

On the second side of the record we experience an even

more magnificent miracle of emergence. From beginning

to end the structures, the atmospheres and the emotionality

of the music change constantly. The primary melody of

Composition No. 358 introduced at the beginning conveys

the feeling that one is moving on a shaky ground that could

break away or mutate into something else at any time. And it

does. The piece was written by Braxton for a three-day engagement

of his 12+1tet at Manhattan’s Iridium. The fiery live

version is documented on the terrific box set 9 Compositions

(Iridium) 2006 (FH12-04-03-001). This is an example of

the fourth species. This last GTM series bears the telling names

Accelerator Class or, in this case, Accelerator Whip. The

corresponding works are characterized by a good portion of

rhythmic uncertainty and divergence. The septet succeeds in

shaping every single moment in a distinctive way. Forms are

created, overwritten, dissolved, sometimes at the same time.

In certain moments the mood is playful and dreamy, then

suddenly the coordinates shift, entropy rises, bubbles and

evaporates. Familiar melodic fragments mix into the atonal

hustle and bustle. After about eight minutes, the fancy march

No. 58, one of Braxton’s most charming orchestral pieces, arrives

from nowhere, mesmerizing the entire ensemble and

throwing it into carnivalesque turmoil for a few minutes. A

section from No. 168 is again interspersed. The musicians

also draw additional rhythmic inspiration from No. 108d, one

of four Pulse Track Structures with which Braxton once used

to destabilize the metric balance of his quartet music.

When the breathtaking lockstep of Composition No. 193

greets us on the third side of this double album, there is no

doubt that we are dealing with the first GTM species. It takes

about five minutes for everyone in the ensemble to gradually

detach themselves from the primary melody. As if they

needed a refreshing breather, they slow down the music and

let the sonic substance become fleeting and transparent like

a fascinating mirage. With new energy and like adventurous

travelers, they pick up speed again afterwards. Compared to

Braxton’s original version, to be heard on Tentet (New York)

1996 (BH004), the basic melody disappears relatively often

from the listening field, but nevertheless it seems to run

through the colorful activities like a red thread. The Pulse

Track Structure No. 108c, the airy slow pulse piece No. 48 and,

shortly before the finale, the dynamic repetition patterns of

No. 6f serve as collage material.

Finally there remains the third species, which, compared to

the second, shows more polyrhythm and incoherence and

less regularity and stringency. The Ghost Trance Septet selected

a previously undocumented example, Composition No.

264. With a fine feeling for contrasting timbres (the choice

of instruments is almost always left to the musicians in the

GTM) and exciting tempo changes, the territories of the score

are executed. The Pulse Track Structure No. 108a, small parts

of the duos No. 101 and No. 304 and two well-known quartet

pieces serve as enrichment material. One of them, the “postbe-

bop thematic structure”, as Braxton says in his Composition

Notes, of No. 40b stands out clearly and distinctly from

the rest of the proceedings after about nine minutes. The repetitive

motif of No. 40o, on the other hand, appears like a

fleeting memory a minute before the end, and no sooner has

it been perceived than it has disappeared.

The Ghost Trance Septet does everything right on this production.

Whereby “right” is not meant in the sense of correctness,

which Braxton dismisses in his recommendations

to performers above, but in the sense of astonishing creative,

daring, lustful, sensitive, and thrilling. How to play Braxton?

Whoever holds this album in his hands can put a very convincing

answer on the record player. Over and over again.

TIMO HOYER

Author of the book Anthony Braxton – Creative Music (Wolke

Verlag, Hofheim 2021)

SIDE A

composition 255

SIDE B

composition 358

SIDE C

composition 193

(+ 108C + 48 + 6F)

Anthony Braxton - 24:47.226

SIDE D

composition 264

total time - 95:22

eNR105 © 2022

DOWNLOADABLES

for professional use

download Band photo

© Kobe Wens (Rainy Days - Luxembourg, 2021)

download track artwork composition 255

© Anthony Braxton and Tri-Centric Foundation

download track artwork composition 358

© Anthony Braxton and Tri-Centric Foundation

download track artwork composition 193

© Anthony Braxton and Tri-Centric Foundation

download track artwork composition 264

© Anthony Braxton and Tri-Centric Foundation